|

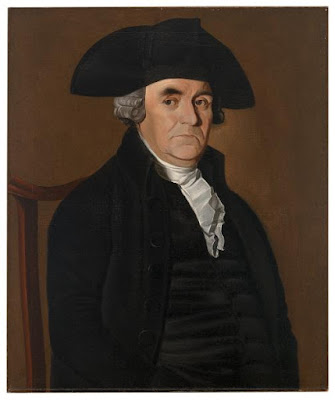

| Portrait of Col. Benjamin Simonds, by William Jennys in 1796. |

~Intro~

Benjamin Simonds (sometimes written Simons, Symons, and Symonds) was among the thirty captives from the siege of Fort Massachusetts in 1746. He was left ill in a hospital in Quebec at the time the surviving captives returned to Boston. He returned later in October of 1747 and was the only former captive to settle in West Hoosac (now Williamstown, MA).

He served in King George's War, the French and Indian War, and the American Revolutionary War. And he was an important figure in the original settlement and early history of Williamstown, Massachusetts.

~Prologue~

Benjamin Simonds' grandfather, Joseph Simonds, and his grand-uncle, James Simonds, both fought in King Philip's War, in 1676. Joseph Simonds became one of the most well to do residents in the part of Cambridge, Massachusetts called Cambridge Farms that would later become the town of Lexington. He was chosen a "survayor for ye high ways" and for "ye farmes." And later, he held other elected positions––"Constable for ye farmes", tithingman, and selectman. After Lexington was incorporated as a town on 20 March 1712/13, he was one of the first five people to be elected a selectman for the new town.

Benjamin Simonds' father, Joseph Simonds Jr., was born in Cambridge Farms. By around 1719, he moved and would become one of the first settlers of the town of Londonderry, New Hampshire––originally settled by Scotch-Irish settlers in a place near Haverhill called Nutfield (because of the many chestnut, butternut, and walnut trees), that would later be renamed Londonderry. He played an active part in the affairs of the new town, having been one of the four men who built the town's first saw-mill. Although Joseph Simonds Jr. apparently had no Scotch-Irish blood, he was assigned the No. 1 lot in the so-called English Range. Shortly after this, about 1723, he moved to the northern part of the town of Killingly, Connecticut, where he settled in an area called Putnam Heights, that would later become the town of Putnam.

Benjamin Simonds was born and baptized in Killingly, Connecticut, on February 23, 1726. His mother, Rachel, died when he was three years old. Around 1740, he and his family––father, brother, and stepmother––relocated to Ware River (now Ware) in Massachusetts.

Benjamin Simonds appeared to have shared some of the same characteristics as his father, his father before him, and his father's father before him, as you will further read.

~King George's War~

During his time at Fort Massachusetts, he was among the thirty captives from the Siege of 1746. They were captured there on August 20, 1746, and carried off to Canada by the French and their Indian allies. The events of the siege and capture––and of the captivity that followed––were recorded by the Reverend John Norton, himself among them, in his book, "The Redeemed Captive: Being a Narrative of the Taking and Carrying Into Captivity."

In West Hoosac, the committee was required, by law, to reserve three house lots, "one for the first-settled minister, one for the ministry, and one for the school, as near the centre of the township as may be with convenience." Each proprietor was required to build a dwelling eighteen by fifteen feet with a seven-foot stud height; clear, plow, and sow five acres of his house-lot with English grass or corn within two years after purchase. A good example of such a dwelling is the 1753 House, a replica of a regulation settler’s home, located in the center of the Route 2 roundabout in Williamstown––very near where Benjamin Simonds built the town's first tavern. Chance, determined by the number drawn, determined the location of each man's purchase. Benjamin Simonds name is seventh on the list of thirteen buyers among the fort's men. And he was one of the first to clear his house-lot, No. 22, at the west end of the future village. It was across Hemlock Brook and a few rods up Buxton Hill, on the south side of the road.

In the spring of 1752, at the age of twenty-six, he married Miss Mary Davis, of Northampton, Massachusetts. They had a daughter who was the first child of European descent to be born in West Hoosac, on April 8, 1753, named Rachel––presumably named after his mother.

It wasn't long before tensions rose once again between the two nations. And, in the spring of 1754, the French and Indian War had begun––pitting the colonies of British America against those of New France.

From late winter of 1754 into the spring of 1755, Colonel Ephraim Williams Jr. (having been appointed colonel of his regiment for this expedition) proceeded to carry out the desires of the governor in respect to the enlistment of men for what was called "Shirley's own Regiment," (formally called the 50th Regiment of Foot) for the Crown Point expedition––one of three great offensive expeditions against the French. And, on May 31st, Governor Shirley ordered Colonel Williams to proceed with his regiment to the "General Rendezvous at Albany, and on their arrival there to follow such orders and directions as they shall receive from Major General William Johnson, Commander in Chief of the Forces raised within the several Provinces and Colonies, for the intended expedition to erect a Fort or Forts on his Majesty's lands near Crown Point, and for the removal of such encroachments as have already been made there by the French." Shortly after arriving at the military rendezvous in Albany, he had his last will and testament drawn, signed, and sealed. In his will, he included a bequest to support and maintain a free school to be established in the town of West Hoosac, provided the town change its name to Williamstown.

Seven weeks later, Colonel Ephraim Williams Jr. was shot and killed during an ambush by the French and their Indian allies in the Battle of Lake George, in an engagement known as "The Bloody Morning Scout", on September 8, 1755.

In Colonel Ephraim Williams Jr's. last will and testament, he included a bequest to support and maintain a free school to be established in the town of West Hoosac, provided the town change its name to Williamstown.

At a proprietors' meeting held May 21, 1765, Benjamin Simonds was appointed to get a copy of Ephraim Williams's last will and testament. The first town-meeting was held July 15, 1765, and West Hoosac was incorporated as Williamstown, in compliance with the will.

The original grant to the Proprietors of West Hoosac was conditional upon their providing, within five years, a church meeting house, and engaging a suitable minister. When the proprietors decided in 1766 (or 1768) to build a church, Mr. Simonds was on the committee to choose the site. They chose The Square as the site, where North and South Streets cross Main Street. In that same year, he was appointed to a committee to choose a new burial-ground. They reported in favor of a lot on the north side of the end of Main Street, beyond Hemlock Brook and opposite the original house of Mr. Simonds, that became known as the Westlawn Cemetery––where his mortal remains were laid to rest.

Benjamin Simonds was instrumental in the founding of the school that would later become Williams College. He was called upon in 1790, when he was sixty-four, for one more notable service to the community. This time it was nothing less than to see that the school was actually built. It took ten years to change the name of the town, and another twenty to settle Williams's estate. Finally, a charter for the Free School was granted, with a board of nine trustees whose first duty was to erect a building. Benjamin Simonds was the only man in town who had known Ephraim Williams Jr. intimately in the old days. "His new task was an obligation of ancient friendship, as well as a duty towards the younger generation coming on." The trustees voted that "Colonel Benjamin Simonds be requested to join said committee in the discharge of their appointment, and that the President be desired to inform the gentleman of this request." Such an appeal by the trustees can only be regarded as an acknowledgment of the Colonel's organizational skills and his reputation for completing any job undertaken.

Professor Arthur Perry, in his book, "Williamstown and Williams College," put it best. He wrote:

Following up to the siege, Reverend Norton commented on the condition of the soldiers and the fort. He wrote:

Again, in Norton's words, their case was this:

The weary journey of the captives had begun mainly under the charge of the Indians, for Vaudreuil could not or did not strictly enforce the first article of his promises. Yet, both the French and the Indians proved to be unexpectedly considerate. Benjamin Simonds, John Aldrich (who was shot through the foot during the fighting), and John Perry's wife (who was in her last month of pregnancy), not having the ability to effectively walk, were transported down the Hoosac River in a canoe at what is now the "River Bend Farm'' in Williamstown, the point farthest up the Hoosac to which any boats were brought in this expedition. It was at this point that the band of captives rested for a while about noon of the first day's march to Canada. "We went about four miles to the place where the army encamped the night before they came upon us," Norton wrote in his book. "Next to Josiah Read, who died a few miles down the river a few hours later, the sickest of the captives was a lad named Benjamin Simonds, then twenty years old, who lived to own the broad meadow, and to build upon it the stately house still standing." [More on that later.]

Norton continues:

Finally arriving in Quebec on September 15th, the captives were transferred to a guard-house in the lower town where there were already about seventy-five other prisoners of war. But in November “a very mortal epidemical fever”, that originated on-board a French man-of-war, reached the guard-house. More than half of the Massachusetts party died. At the end of July, the survivors sailed for Boston under a flag of truce on the ship Vierge-de-Grace, and arriving on August 16, 1747, exactly thirty years before the Battle of Bennington. [More on that later, also.]

Benjamin Simonds and John Aldrich*, however, too sick to be moved, were left behind in the hospital at Quebec. Mr. Simonds returned later in October of 1747.

* "John [Aldrich] was taken by Indians to Canada from the Fort at Hoosac which after a battle of 25 hours with 800 French and Indians surrendered on capitulation prisoners of war in the summer or fall of 1746. He was brought in the 5th of Oct., near Quebec, taken from Nehemiah Howes captivity. How long he remained a prisoner with the Indians cannot be ascertained. Later he was befriended by an old Indian and returned home to Northbridge, MA."- George Aldrich Genealogy, Vol. 1, p. 62.

With the close of King George's War in late 1748, it allowed for the opportunity to establish townships. After the boundaries of the two townships had been surveyed in April of 1749, then designated as "East Hoosac" and "West Hoosac", village lots were then established the following year by a committee appointed by the General Court, "for admitting settlers in the West New Township of Hoosuck".

Although his father had given him a farm of seventy acres on "Muddy Brook" in Ware, Massachusetts, after his return, Benjamin Simonds chose to return to the Hoosac Valley. Fort Massachusetts had been rebuilt, and it needed to be fully garrisoned. Perhaps he also knew of an opportunity of settling on the nearby land.

The doctor [Captain Ephraim Williams, Jr.'s brother, Dr. Thomas Williams] with fourteen men went off for Deerfield [Massachusetts], and left in the fort Sergeant John Hawks with twenty soldiers [And eight women and children––families of some of the soldiers––were there as well.], about half of them sick with bloody flux. Mr. Hawks sent a letter by the doctor to the captain, supposing that he was then at Deerfield, desiring that he would speedily send up some stores to the fort, being very short on it for ammunition, and having discovered some signs of the enemy; but the letter did not get to the captain seasonably. This day also, two of our men being out a few miles distant from the fort discovered the tracks of some of the enemy.Three days later, the French and their Indian allies had launched their attack. Yet, despite the state of the fort and its inhabitants, the soldiers put up a stubborn fight for thirty hours. The French commander, Monsieur Rigaud de Vaudreuil, asked for a parley. The fort had only three or four pounds of powder left, and “prayers to God for wisdom and direction, we considered our case.”

Again, in Norton's words, their case was this:

Had we all been in health, or had there been only those eight of us that were in health, I believe every man would willingly have stood it out to the last. For my part I should; but we heard that if we were taken by violence, the sick, the wounded, and the women would most, if not all of them, die by the hands of the savages; therefore our officer concluded to surrender on the best terms he could get …Those terms were as follows:

I. That we should be all prisoners to the French; the General promisingVaudreuil also promised, “that those who were weak and unable to travel should be carried in their journey.” This was a bit of good luck for Benjamin Simonds because he was incapacitated with dysentery.

that the savages should have nothing to do with any of us.

II. That the children should all live with their parents during the time of

their captivity.

III. That we should all have the privileges of being exchanged the first

opportunity that presented.

The weary journey of the captives had begun mainly under the charge of the Indians, for Vaudreuil could not or did not strictly enforce the first article of his promises. Yet, both the French and the Indians proved to be unexpectedly considerate. Benjamin Simonds, John Aldrich (who was shot through the foot during the fighting), and John Perry's wife (who was in her last month of pregnancy), not having the ability to effectively walk, were transported down the Hoosac River in a canoe at what is now the "River Bend Farm'' in Williamstown, the point farthest up the Hoosac to which any boats were brought in this expedition. It was at this point that the band of captives rested for a while about noon of the first day's march to Canada. "We went about four miles to the place where the army encamped the night before they came upon us," Norton wrote in his book. "Next to Josiah Read, who died a few miles down the river a few hours later, the sickest of the captives was a lad named Benjamin Simonds, then twenty years old, who lived to own the broad meadow, and to build upon it the stately house still standing." [More on that later.]

Norton continues:

Here we sat down for a considerable time. My heart was filled with sorrow, expecting that many of our weak and feeble people would fall by the merciless hands of the enemy. And as I frequently heard the savages shouting and yelling, trembled, concluding that they then murdered some of our people. And this was my only comfort, that they could do nothing against us, but what God in his holy Providence permitted them; but was filled with admiration when I saw all the prisoners come up with us, and John Aldrich carried upon the back of his Indian master.By their third day's march, the Indians found horses for Benjamin Simonds and John Aldrich.

Finally arriving in Quebec on September 15th, the captives were transferred to a guard-house in the lower town where there were already about seventy-five other prisoners of war. But in November “a very mortal epidemical fever”, that originated on-board a French man-of-war, reached the guard-house. More than half of the Massachusetts party died. At the end of July, the survivors sailed for Boston under a flag of truce on the ship Vierge-de-Grace, and arriving on August 16, 1747, exactly thirty years before the Battle of Bennington. [More on that later, also.]

Benjamin Simonds and John Aldrich*, however, too sick to be moved, were left behind in the hospital at Quebec. Mr. Simonds returned later in October of 1747.

* "John [Aldrich] was taken by Indians to Canada from the Fort at Hoosac which after a battle of 25 hours with 800 French and Indians surrendered on capitulation prisoners of war in the summer or fall of 1746. He was brought in the 5th of Oct., near Quebec, taken from Nehemiah Howes captivity. How long he remained a prisoner with the Indians cannot be ascertained. Later he was befriended by an old Indian and returned home to Northbridge, MA."- George Aldrich Genealogy, Vol. 1, p. 62.

~Settling in West Hoosac~

With the close of King George's War in late 1748, it allowed for the opportunity to establish townships. After the boundaries of the two townships had been surveyed in April of 1749, then designated as "East Hoosac" and "West Hoosac", village lots were then established the following year by a committee appointed by the General Court, "for admitting settlers in the West New Township of Hoosuck".

Although his father had given him a farm of seventy acres on "Muddy Brook" in Ware, Massachusetts, after his return, Benjamin Simonds chose to return to the Hoosac Valley. Fort Massachusetts had been rebuilt, and it needed to be fully garrisoned. Perhaps he also knew of an opportunity of settling on the nearby land.

In West Hoosac, the committee was required, by law, to reserve three house lots, "one for the first-settled minister, one for the ministry, and one for the school, as near the centre of the township as may be with convenience." Each proprietor was required to build a dwelling eighteen by fifteen feet with a seven-foot stud height; clear, plow, and sow five acres of his house-lot with English grass or corn within two years after purchase. A good example of such a dwelling is the 1753 House, a replica of a regulation settler’s home, located in the center of the Route 2 roundabout in Williamstown––very near where Benjamin Simonds built the town's first tavern. Chance, determined by the number drawn, determined the location of each man's purchase. Benjamin Simonds name is seventh on the list of thirteen buyers among the fort's men. And he was one of the first to clear his house-lot, No. 22, at the west end of the future village. It was across Hemlock Brook and a few rods up Buxton Hill, on the south side of the road.

In the spring of 1752, at the age of twenty-six, he married Miss Mary Davis, of Northampton, Massachusetts. They had a daughter who was the first child of European descent to be born in West Hoosac, on April 8, 1753, named Rachel––presumably named after his mother.

~The French and Indian War~

It wasn't long before tensions rose once again between the two nations. And, in the spring of 1754, the French and Indian War had begun––pitting the colonies of British America against those of New France.

From late winter of 1754 into the spring of 1755, Colonel Ephraim Williams Jr. (having been appointed colonel of his regiment for this expedition) proceeded to carry out the desires of the governor in respect to the enlistment of men for what was called "Shirley's own Regiment," (formally called the 50th Regiment of Foot) for the Crown Point expedition––one of three great offensive expeditions against the French. And, on May 31st, Governor Shirley ordered Colonel Williams to proceed with his regiment to the "General Rendezvous at Albany, and on their arrival there to follow such orders and directions as they shall receive from Major General William Johnson, Commander in Chief of the Forces raised within the several Provinces and Colonies, for the intended expedition to erect a Fort or Forts on his Majesty's lands near Crown Point, and for the removal of such encroachments as have already been made there by the French." Shortly after arriving at the military rendezvous in Albany, he had his last will and testament drawn, signed, and sealed. In his will, he included a bequest to support and maintain a free school to be established in the town of West Hoosac, provided the town change its name to Williamstown.

Seven weeks later, Colonel Ephraim Williams Jr. was shot and killed during an ambush by the French and their Indian allies in the Battle of Lake George, in an engagement known as "The Bloody Morning Scout", on September 8, 1755.

In January of 1756, a proposal was sent to the General Court of Massachusetts for aid to erect a blockhouse in West Hoosac. Benjamin Simonds, and a few other capable ax-men, built the new block-house in one month. It was referred to as 'West Hoosac Fort'. It stood very near the present Williams Inn. Benjamin Simonds served as garrison soldier and member of the Council of Public Safety until the fort was abandoned in 1761.

Fort Massachusetts was decommissioned following the Battle of Quebec in 1759. And by the close of the French and Indian War, in 1760, most of the fighting had ended in North America. The war in North America officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on February 10, 1763.

The outcome of the French and Indian War established British control of North America and gave birth to the British Empire. And it also triggered the movement towards independence for the British colonists in America.

Benjamin Simonds was laying the foundations in his increasing property, in his general enterprise and public spirit, and in his broadening acquaintance as a tavern-keeper.

In 1764, Mr. Simonds purchased Lot No. 3 from Timothy Woodbridge, and built and operated the first tavern in town there, on or near the site now occupied by the David & Joyce Milne Public Library. A tavern provided rudimentary lodging, food, and drinks for travelers, and also provided a meeting place for the settlers. By 1765, he owned six other house lots close by, on both sides of Hemlock Brook, including No. 22, his original purchase and on which he built his first house. And he built the River Bend Tavern a mile north of The Square in the White Oaks neighborhood, in 1769. This was the same location where he, and his fellow captives from Fort Massachusetts, in 1746, rested for a while on their first day's march to Canada. The "Col. Benjamin Simond House" was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983, and now houses a bed and breakfast.Fort Massachusetts was decommissioned following the Battle of Quebec in 1759. And by the close of the French and Indian War, in 1760, most of the fighting had ended in North America. The war in North America officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on February 10, 1763.

The outcome of the French and Indian War established British control of North America and gave birth to the British Empire. And it also triggered the movement towards independence for the British colonists in America.

~Laying the Foundations~

Benjamin Simonds was laying the foundations in his increasing property, in his general enterprise and public spirit, and in his broadening acquaintance as a tavern-keeper.

~The Founding of Williamstown~

In Colonel Ephraim Williams Jr's. last will and testament, he included a bequest to support and maintain a free school to be established in the town of West Hoosac, provided the town change its name to Williamstown.

At a proprietors' meeting held May 21, 1765, Benjamin Simonds was appointed to get a copy of Ephraim Williams's last will and testament. The first town-meeting was held July 15, 1765, and West Hoosac was incorporated as Williamstown, in compliance with the will.

The original grant to the Proprietors of West Hoosac was conditional upon their providing, within five years, a church meeting house, and engaging a suitable minister. When the proprietors decided in 1766 (or 1768) to build a church, Mr. Simonds was on the committee to choose the site. They chose The Square as the site, where North and South Streets cross Main Street. In that same year, he was appointed to a committee to choose a new burial-ground. They reported in favor of a lot on the north side of the end of Main Street, beyond Hemlock Brook and opposite the original house of Mr. Simonds, that became known as the Westlawn Cemetery––where his mortal remains were laid to rest.

~The American Revolutionary War~

The War of the Revolution again aroused the patriotic spirit of Benjamin Simonds, and he joined the ranks in defense of his country and bravely fought in the American Revolutionary War. The American War of Independence––the war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and its former 13 united British colonies in North American––was fought from 1775 to 1783.

He was commissioned colonel of the of the 2nd Berkshire County Regiment of Massachusetts Militia, of about five hundred men known as the "Berkshire Boys" between 1775 and 1777, while Colonel Mark Hopkins was commissioned colonel of the 1st Berkshire County Regiment. Colonel Simonds's regiment was involved in a number of battles, raids, skirmishes, and expeditions, of which only a few will be mentioned in this article.

In the summer of 1776, Major General Horatio Gates, and Generals Philip Schuyler, and Benjamin Lincoln were corresponding directly with Colonel Simonds concerning the defense of upper New York State against the rumored advance of the British from Montreal. By October, both Berkshire regiments were ordered to join Washington's forces at White Plains, where they fought in the fatal Battle of White Plains––Colonel Mark Hopkins was taken sick with a fever at White Plains and died there, October 26th, only two days before the memorable battle took place.

He was commissioned colonel of the of the 2nd Berkshire County Regiment of Massachusetts Militia, of about five hundred men known as the "Berkshire Boys" between 1775 and 1777, while Colonel Mark Hopkins was commissioned colonel of the 1st Berkshire County Regiment. Colonel Simonds's regiment was involved in a number of battles, raids, skirmishes, and expeditions, of which only a few will be mentioned in this article.

In the summer of 1776, Major General Horatio Gates, and Generals Philip Schuyler, and Benjamin Lincoln were corresponding directly with Colonel Simonds concerning the defense of upper New York State against the rumored advance of the British from Montreal. By October, both Berkshire regiments were ordered to join Washington's forces at White Plains, where they fought in the fatal Battle of White Plains––Colonel Mark Hopkins was taken sick with a fever at White Plains and died there, October 26th, only two days before the memorable battle took place.

Simonds's Regiment was then ordered north to Fort Ticonderoga and was stationed there from December 16, 1776, to March 22, 1777. The winter of 1776-1777 was a brutal one. Men nearly froze to death in the unheated stone buildings and log huts and tents around the fort. And with four weakened regiments––totaling twelve hundred men and boys, of whom three hundred were due to depart––their commander could do little more than mount guards, send out scouts, and scavenge for firewood.

In April, both Berkshire regiments (the 1st Berkshire County Regiment led by Captain John Spoor, who replaced Colonel Mark Hopkins) marched by orders of Major General Gates, to assist General Schuyler in Saratoga in what would become known as the Saratoga Campaign––an attempt by the British to gain control over the advantageous Hudson River Valley, and isolate New England from the rest of the colonies.

On August 13, 1777, Colonel Simonds met with General John Stark and Colonel Seth Warner in a council of war at the "Catamount Tavern" before fighting in his most momentous of engagements, and one of the early pivotal battles of the American Revolutionary War––the Battle of Bennington.

For two months, General John Burgoyne led his army down Lake Champlain and the Hudson River toward Albany, New York––and was initially a success for the British. However, he found his army was in desperate need of some provisions and horses. So he sent a mixed force of about 800 Canadians, Loyalists, Indians, British, and Hessian (German) mercenaries, under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum, on a foraging expedition to Manchester, Vermont. However, at the last moment, Burgoyne ordered him to not march on Manchester, but on Bennington. The Lieutenant-General had just learned from one of his Tory captains that there was an important magazine of rebel supplies, live cattle, horses, and flour, that were lightly guarded by three or four hundred militia in Bennington.

On the afternoon of August 16, the fighting broke out, and Baum's position was immediately surrounded by gunfire, which Stark described as "the hottest engagement I have ever witnessed, resembling a continual clap of thunder."

In October of 1781, the American Revolutionary War had come to an end with the Siege of Yorktown. And two years later, the Treaty of Paris was signed and made it official: the United States of America had become a free, independent, and sovereign nation.

In April, both Berkshire regiments (the 1st Berkshire County Regiment led by Captain John Spoor, who replaced Colonel Mark Hopkins) marched by orders of Major General Gates, to assist General Schuyler in Saratoga in what would become known as the Saratoga Campaign––an attempt by the British to gain control over the advantageous Hudson River Valley, and isolate New England from the rest of the colonies.

On August 13, 1777, Colonel Simonds met with General John Stark and Colonel Seth Warner in a council of war at the "Catamount Tavern" before fighting in his most momentous of engagements, and one of the early pivotal battles of the American Revolutionary War––the Battle of Bennington.

For two months, General John Burgoyne led his army down Lake Champlain and the Hudson River toward Albany, New York––and was initially a success for the British. However, he found his army was in desperate need of some provisions and horses. So he sent a mixed force of about 800 Canadians, Loyalists, Indians, British, and Hessian (German) mercenaries, under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum, on a foraging expedition to Manchester, Vermont. However, at the last moment, Burgoyne ordered him to not march on Manchester, but on Bennington. The Lieutenant-General had just learned from one of his Tory captains that there was an important magazine of rebel supplies, live cattle, horses, and flour, that were lightly guarded by three or four hundred militia in Bennington.

On the afternoon of August 16, the fighting broke out, and Baum's position was immediately surrounded by gunfire, which Stark described as "the hottest engagement I have ever witnessed, resembling a continual clap of thunder."

By the end of the day, the British foraging expedition force was essentially annihilated, reducing Burgoyne's army by almost 1,000 men. The defeat at Bennington greatly discouraged Burgoyne's uneasy Indian allies, who largely abandoned him, and deprived him of supplies, leaving him in a more dangerous position than before.

Three months later, Colonel Simonds's regiment would continue on to the Battle of Bemis Heights. And on October 17th, Gen. Burgoyne surrendered his entire army following his humiliating defeat at the decisive Battle of Saratoga.

Three months later, Colonel Simonds's regiment would continue on to the Battle of Bemis Heights. And on October 17th, Gen. Burgoyne surrendered his entire army following his humiliating defeat at the decisive Battle of Saratoga.

In October of 1781, the American Revolutionary War had come to an end with the Siege of Yorktown. And two years later, the Treaty of Paris was signed and made it official: the United States of America had become a free, independent, and sovereign nation.

|

| The Bennington Monument and marker in Bennington, Vermont -- the marker recognizing Col. Benjamin "Symonds". |

|

| Bas-relief of the Battle of Bennington, at the Bennington Battleground Historic Site in New York Sculpture by William Gordon Huff. |

~The Founding of Williams College~

Professor Arthur Perry, in his book, "Williamstown and Williams College," put it best. He wrote:

. . . As the Free School was conceived of by Colonel Ephraim Williams and described in terms in his will drawn and probated in 1755, it was designed for the direct benefit of the children of the soldiers, who had served under him in one or other of the forts of the old French line. Simonds had two children born to him in West Hoosac while Colonel Williams was still in command of the line of forts, and before he had set his face toward the fatal field of Lake George. It is perhaps more than likely that Colonel Williams had spoken at one time or another to his well-known subordinate and fellow-proprietor in West Hoosac (their house-lots were in plain sight of each other on either side of Hemlock Brook) of his intention to do something handsome for the children of the hamlet, inasmuch as he himself was a barren stock. At all events, now that Colonel Williams had been thirty-five years in his grave by the lakeside, and his benefaction was just coming into efficacy on behalf of somebody's children, how natural it was for the trustees to put themselves into practical consultation with the only man then living in Williamstown who had known the donor personally and perhaps even intimately.

Aside from the fact that Colonel Simonds seemed to represent directly and personally those whom Colonel Williams had in mind to benefit a whole generation before, he seemed also to represent better than anybody else present the entire inhabitants of the borough, as the benevolence of the founder was beginning to be displayed before their eyes. It was primarily a local benefaction; it should, therefore, be adapted to the local wants and habits, as they should judge these to be who were most familiar with the past and present of the little village and with the prejudices and opinions of the people.

The building of what is now referred to as "West College" began in the early summer of 1790 and was more or less finished by the winter of 1790-91. The school opened on October 20, 1791, and was named the “Free School”.

Not long after its founding, the school's trustees petitioned the Massachusetts legislature to convert the free school to a tuition-based college. The legislature agreed, and on June 22, 1793, Williams College was chartered. It was the second college to be founded in Massachusetts. And Williams College is regarded as a leading institution of higher education in the United States.

Although Benjamin Simonds's children had not attended the school, a number of his descendants have.

Benjamin Simonds was assuredly a man of sound judgment and executive ability, as demonstrated through both his military service and community involvement. And, like his great-grandfather, William Simonds, and his grandfather, Joseph Simonds Sr., and his father, Joseph Simonds Jr., before him, he too was a pioneer.

As far as I know, he kept no diary. So we don't know what his daily routine was on a given day, or what he thought about this or that. We do have a fine portrait of the Colonel (featured at the beginning of this article), that was painted in 1796 when he was seventy years old. But can you accurately assess a person's character or personality based on their facial features from a portrait painting? "Any revelation to be found came through action; all else have perished."

I'll close with the following taken from Bliss Perry's [Benjamin Simonds's great-great-great-grandson] book, “Colonel Benjamin Simonds, 1726-1807”. He wrote:

Related Links:

Sources:

Photo credits:

Not long after its founding, the school's trustees petitioned the Massachusetts legislature to convert the free school to a tuition-based college. The legislature agreed, and on June 22, 1793, Williams College was chartered. It was the second college to be founded in Massachusetts. And Williams College is regarded as a leading institution of higher education in the United States.

Although Benjamin Simonds's children had not attended the school, a number of his descendants have.

~Beyond the River Bend~

Benjamin Simonds moved from the River Bend Tavern and bought a house just a stone's throw away––Pine lot No. 1, at the junction of the North Hoosac Road with the Simonds Road––built in 1773 by Robert Hawkins. Colonel Simonds lived in it during the last ten years of his life with his second wife, Anna. His daughter, Rachel and her second husband, Benjamin Skinner, whom she had married after the death of her first husband, Thomas Train, took charge of the tavern.

|

| As it looked in the 1880s. |

Benjamin and Mary (Davis) Simonds had seven daughters and three sons, all born in Williamstown, Massachusetts. She died in June of 1798. He later married Anna (Collins) Putnam, of Brimfield, Massachusetts, widow of Asa Putnam, in November of 1798, bringing her children into his family (at the time, her three youngest, while her oldest son was already settled in Williamstown.) They did not have any children together. She died on April 3, 1807. Colonel Benjamin Simonds died a week later.

Sylvia Putnam Hamilton, who was seventeen years old when both her mother and the Colonel died, recollected—in her old age—that the Colonel did not care to live after her mother died.

Professor Arthur Perry, in his book, "Origins in Williamstown," wrote;

Mrs. Hamilton [Benjamin Simonds's step-daughter] communicated other pleasant recollections of Colonel Simonds in her girlhood: such as, for example, he always wore

his military costume more or less complete till the last, as it appears in his portrait, — the cocked hat and powdered wig, the white neck-kerchief and frilled shirt-bosom, the regimental coat and buttons, and also the short-clothes and knee-buckles; he always

went to church in full costume; and he occasionally offered family prayers, standing by the back of his chair. The late Dr. Morgan, of Bennington, told the writer that when he was a small boy riding past with his father, he had repeatedly seen the Colonel sitting in

summer in his front doorway in his military toggery, being saluted by, and saluting in turn, the passers-by.

The section of route 7, in Williamstown, stretching straight from the bridge, past his house, to the Pownal, Vermont line, is named "Simonds Road" in his memory.

And also, one of the tall peaks that surround Mount Greylock, the highest point in Massachusetts, was named in his honour—"Simonds Peak".

Epilogue

Benjamin Simonds was assuredly a man of sound judgment and executive ability, as demonstrated through both his military service and community involvement. And, like his great-grandfather, William Simonds, and his grandfather, Joseph Simonds Sr., and his father, Joseph Simonds Jr., before him, he too was a pioneer.

As far as I know, he kept no diary. So we don't know what his daily routine was on a given day, or what he thought about this or that. We do have a fine portrait of the Colonel (featured at the beginning of this article), that was painted in 1796 when he was seventy years old. But can you accurately assess a person's character or personality based on their facial features from a portrait painting? "Any revelation to be found came through action; all else have perished."

I'll close with the following taken from Bliss Perry's [Benjamin Simonds's great-great-great-grandson] book, “Colonel Benjamin Simonds, 1726-1807”. He wrote:

Fictionalized biography of the present day tries to make us see what was in the mind of their personages in the closing years or hours of life. The last chapter of Lytton Strachey's Queen Vistoria is a well known example of this "stream of consciousness" technique. But I question whether either Stachey or Virginia Woolf could have persuaded us to believe what really passed through the Colonel's mind as he sat there, reviewing his career. Was it the tomahawks of his Indian captors? The French grandees at Quebec? That first cabin with Mary Davis beyond Hemlock Brook? Washington's impassive face as he retreated at White Plains? The stolid Hessians in the Tory redoubt? Building a church of which he was not a member, or a West College which a grandson might some day enter? Rum at two shillings a gallon? The answer is that no one knows or can possibly know.

. . . .

The tombstone of Benjamin Simonds is in the West [Lawn] Cemetery, across Hemlock Brook, and nearly opposite the site of his first cabin. The dates of birth and death are given, and then the midest and proud words: "A firm suppoorter of his country's independence." More than one man, not of the Colonel's blood, has made a pilgrimage to the West [Lawn] Cemetery simply to read that inscription, and to restore his soul.

~In Memoriam~

|

| Headstone of Benjamin Simonds, at West Lawn Cemetery, Williamstown, MA |

The epitaph of Benjamin Simonds is as follows: —

This monument erected

in memory of Col.

BENJAMIN SIMONDS,

one of the first settlers in

Williamstown, and a firm sup

porter of his Country's indepen

dence. He was born Feb. 23rd

1726, and died April 11th 1807.

“What man is he that liveth, and shall not see death? Shall

he deliver his soul from the hand of the grave?” Psalm 89:48

Related Links:

- A Brief History of Fort Massachusetts: With an Emphasis on the Siege of 1746

- Williamstown Historical Museum

- River Bend Farm Bed & Breakfast

- Winter Soldiering in the Lake Champlain Valley

- Berkshire at Bennington

- Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site

- The Bennington Battle Monument

- "West College" Photographs–> West College and Main Street, 1898, West College, 1898

- Find A Grave Memorial –> Colonel Benjamin Simonds

Sources:

- "Genealogical Sketch of William Simonds," by Edward Johnson, 1889

- "Historic Homes and Places and Genealogical and Personal Memoirs. Relating to the Families of Middlesex County, Massachusetts," by William Richard Cutter 1908

- "The Records of the Town of Cambridge (Formerly Newtowne) Massachusetts, 1630-1703: The Records of the Town Meetings, and of the selectmen, comprising all of the First Volume of Records, and being Volume II of the Printed Records of the Town." 1901

- "The Redeemed Captive: Being a Narrative of the Taking and Carrying Into Captivity," by the Reverend Mr. John Norton -- Published 1870 (Originally published in 1748)

- "Origins in Williamstown," by Arthur Latham Perry -- Published 1894

- "Williamstown and Williams College," by Arthur Latham Perry -- Published 1899

- “Colonel Benjamin Simonds, 1726-1807,” by Bliss Perry [Benjamin Simonds' great-great-great-grandson], 1944 (privately printed)

- "A Narrative of the Captivity of Nehemiah How in 1745-1747," by Nehemiah How -- Published 1904 (Originally published in 1748)

- "General Register of the Society of Colonial Wars, 1899-1902: Constitution of the General Society", General Society of Colonial Wars (U.S.) H. K. Brewer & Company, 1902 - United States

- "Scotch-Irish in New England," by Arthur Latham Perry, J.S. Cushing & Company, 1891 - New England

- "Scotch Irish Pioneers in Ulster and America," by Charles Knowles Bolton, Read Books Ltd, Apr 16, 2013

- "The Barbour Collection of Connecticut Town Vital Records, vol. 20, Huntington (1789-1850), Kent (1739-1852), and Killingly (1708-1850)," (Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1999), 357 (Vol. 1, p. 15 in the original vital records for Killingly, CT). Lorraine Cook White, ed.

- “Colonel Benjamin Simonds: The Battle of White Plains, October 28, 1776,” by Harriet Osborne Putnam [Benjamin Simonds' step-great-great-granddaughter]. The American Monthly Magazine by Daughters of the American Revolution, Volume 3, R.R. Bowker Company, 1893

- "The works of Samuel Hopkins: A Memoir of His Life and Character, Volume 1," by Samuel Hopkins, Edwards Amasa Park, Doctrinal Tract and Book Society, 1854

- "Fort Ticonderoga: A Short History," Compiled from Contemporary Sources by S. H. P. Pell, Reprinted for the Fort Ticonderoga Museum, 1966

- "Those Turbulent Sons of Freedom: Ethan Allen's Green Mountain Boys and the American Revolution," by Christopher S. Wren, Simon and Schuster, May 8, 2018

- "The Incorporation of the Town of Mount Washington & its Soldiers of the Revolutionary War," by Michele (Patterson) Valenzano February 2007

- "The Turning Point of the Revolution," by Hoffman Nickerson, Port Washington, N.Y., Kennikat Press, 1928

- "Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War," A compilation from the archives," (Volume 14), Prepared and published by the Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., State Printers. 1906

- "Williamstown the First 250 Years 1753 - 2003," by Robert R. R. Brooks (Editor), 2005 Williamstown House of Local History.

- "The Hoosac Valley: Its Legends and Its History," by Grace Greylock Niles -- Published 1912

- U.S. News & World Report: Best Colleges––Williams College

- Portrait of Col. Benjamin Simonds, by William Jennys in 1796. It is part of the Williams College Portrait Collection of the Williams College Museum of Art.

- Benjamin Simonds original house on Lot 22, by Noyes, from the book, "Origins in Williamstown," by Arthur Latham Perry -- Published 1894

- Benjamin Simonds' River Bend Tavern/home was taken, with kind permission, from the River Bend Farm website.

- The Hawkins House, by R.H.N. Sc., from the book, "Williamstown and Williams College," by Arthur Latham Perry -- Published 1899

- Bennington Monument marker, in Bennington, Vermont, was taken by Michael Herrick, August 13, 2006.

- Bas-relief of the Battle of Bennington, at the Bennington Battleground Historic Site in Walloomsac, New York was taken by C.A. Chicoine, October 2018.

- Headstone of Benjamin Simonds, at West Lawn Cemetery, Williamstown, Massachusetts, was taken by C.A. Chicoine, October 2018.